Chapter 7 of Spaces: Exploring Spatial Experiences of Representation and Reception in Screen Media, edited by Ian Christie (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2024), adapted from a public lecture at Jesus College, University of Cambridge on 18 October 2018 and presented here with the images that accompanied the lecture.

Abstract

The chapter relates the evolution of its author’s mode of filmmaking, in which sequences of actuality footage of urban and rural landscapes are accompanied by spoken narration written after the footage has been edited. The resulting films – initially short fictions, then feature-length critiques of England’s economy and culture – were accompanied by a growing awareness of the medium’s limitations in representing spatial subjects. Attempts to counter film’s essential linearity were encouraged by two texts – one a well-known passage from Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy; the other a quotation from a 1967 essay by John Berger that became a founding text for contemporary geographers – and by experience realising installations in which moving images were displayed simultaneously on multiple screens.

*

When I began making moving images, I didn’t have much idea what, if anything, I would do with the footage. As a former or at least temporarily lapsed architect, I was attracted not so much by the medium’s capacity to represent space, as by the possibility it offered to capture particular kinds of spatial experience, and it seemed to me that this was achieved primarily through cinematography. I wasn’t very interested in narrative, although most of the films I had in mind were narrative films: some were films noirs, and most monochrome or, if not, Technicolor. I was in the habit of identifying buildings and similar spatial structures with architectural and other qualities that were conventionally overlooked, a genre of quasi-Surrealist ‘found architecture’ that seemed to involve – when I came to know of it – the conceptual transformation that for Louis Aragon was confirmed by the Surrealists’ frisson.1 I collected a canon of texts describing the phenomenon that I have quoted repeatedly ever since,2 among which are passages in Walter Benjamin’s essay ‘Surrealism’ (1929), in which he writes that ‘it is a cardinal error to believe that, of “Surrealist experiences”, we know only the religious ecstasies or the ecstasies of drugs’ and that ‘the true, creative overcoming of religious illumination certainly does not lie in narcotics. It resides in a profane illumination, a materialistic, anthropological inspiration…’3 In life, such moments of altered awareness are typically very fleeting, but it seemed to me that in photographs and, even more so, in films, something similar could be captured.

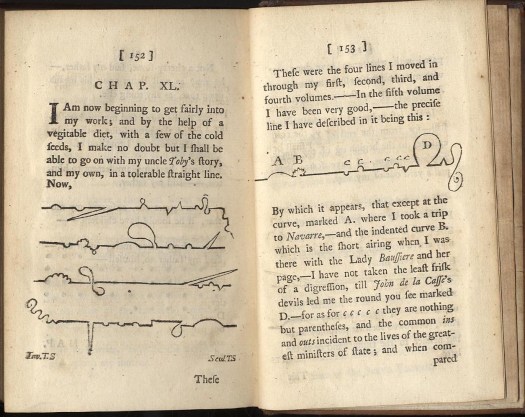

Photography of architecture and landscape typically involves large camera formats and high-resolution, often high-contrast images, as if in pursuit of illusory three-dimensionality. I was used to 35mm colour transparencies, smaller, but without the generational loss involved in making a print. In comparison, the 16mm cine frame was quantitatively challenged.4 My subjects also rarely moved – the first footage I dared exhibit was of a few seconds of a building’s demolition. The first completed film, on the other hand, comprised two ten-minute walks with a hand-held camera, for which I wrote and recorded fictional narration.5 There were similar phantom walks in subsequent films, but in each the camera was increasingly, and eventually almost always, static, each set-up a space within which movement might occur. Edits were more frequent, and narration – initially part sound effect, part attempt at genre – became more important for continuity. As the cinematography was largely spontaneous, the result of mostly unplanned encounters with a variety of landscapes and other structures, I reasoned that the script should be written only after the pictures had been photographed and fine cut.6 This method had the advantage that only a little footage was discarded in editing, but it was difficult to compose coherent text for such a relatively rapid succession of unconnected images and locations. I was encouraged by a passage in Sterne’s Tristram Shandy:

‘For if you will turn your eyes inwards upon your mind … and observe attentively, you will perceive, brother, that whilst you and I are talking together, and thinking and smoaking our pipes: or whilst we receive successively ideas in our minds, we know that we do exist . . . Now, whether we observe it or no, continued my father, in every sound man’s head, there is a regular succession of ideas of one sort or other, which follow each other in train just like—A train of artillery? said my uncle Toby.—A train of a fiddle-stick!—quoth my father,—which follow and succeed one another in our minds at certain distances, just like the images in the inside of a lanthorn turned round by the heat of a candle—’ 7

In an essay about Sterne and Ignatius Sancho, Sukhdev Sandhu has written: ‘Linearity, Sterne believed, amounted to little more than selfishness. In contrast, he felt that we must look around us, be prepared to halt, be diverted by what is going on in the corners, the crevices, the byways of life. These side routes are full of value, pleasure, goodness. . .’ 8 As Sterne wrote: ‘In a word, my work is digressive, and it is progressive too.’9 This, and the succession of ideas, seemed to legitimise the sporadic character of the narration I was trying to write. 10

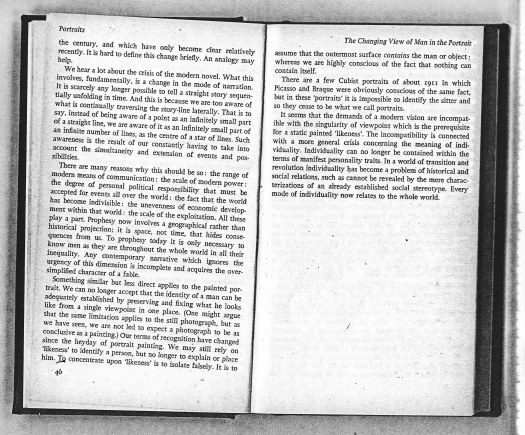

London,11 the first of several longer films, was released in 1994, and reached a wider audience than any of its predecessors. In November that year I presented it at a screening for the London Group of Historical Geographers,12 and in the following January at Parisian Fields, a conference at the University of Kent arranged by Michael Sheringham to coincide with the publication of Jacques Reda’s The Ruins of Paris in English translation.13 A few months later, I was to begin the cinematography for a sequel to London that was completed as Robinson in Space.14 Like most of their shorter predecessors, these two films relied on journeys to structure their unscripted production, but differ in that they have non-fiction subjects, were photographed in 35mm colour, and are narrated by their unseen protagonist’s unseen companion, rather than by the unseen protagonist himself. They were much more expensive, undertaken as commissions from producing institutions, and as a result involved a good deal of preparation. London, Robinson in Space and the later Robinson in Ruins,15 are all fictional accounts of research by a would-be scholar called Robinson into a series of ‘problems’ – in London the ‘problem’ of London, in Robinson in Space the ‘problem’ of England; while in Robinson in Ruins, the problem is perhaps that of dwelling. Robinson in Space was to involve a search for sites of surviving UK manufacturing industry and visits to many ports, in an effort to discover how the country managed to sustain its material economy. I must have mentioned some of this to Michael, and he suggested I might have a look at Edward Soja’s Postmodern Geographies. Between trains in London on the way home, I went into a branch of Waterstones and started reading the first chapter, in which Soja quotes two paragraphs from John Berger’s essay ‘No More Portraits’: 16

‘We hear a lot about the crisis of the modern novel. What this involves, fundamentally, is a change in the mode of narration. It is scarcely any longer possible to tell a straight story sequentially unfolding in time. And this is because we are too aware of what is continually traversing the story-line laterally. That is to say, instead of being aware of a point as an infinitely small part of a straight line, we are aware of it as an infinitely small part of an infinite number of lines, as the centre of a star of lines. Such awareness is the result of our constantly having to take into account the simultaneity and extension of events and possibilities.

‘There are many reasons why this should be so: the range of modern means of communication: the scale of modern power: the degree of personal political responsibility that must be accepted for events all over the world: the fact that the world has become indivisible: the unevenness of economic development within that world: the scale of the exploitation. All these play a part. Prophesy now involves a geographical rather than historical projection; it is space, not time, that hides consequences from us. To prophesy today it is only necessary to know men as they are throughout the whole world in all their inequality. Any contemporary narrative which ignores the urgency of this dimension is incomplete and acquires the over-simplified character of a fable.’ 17

Soja’s emphasis, and that of other geographers, was on the assertion ‘it is space, not time, that hides consequences from us’, though I was just as enthusiastic about Berger’s observation of a change in the mode of narration. I didn’t read the rest of Soja’s book until long after I’d made the film, and never knew exactly why Michael had recommended it: perhaps for the insights that ‘to speak of the “post-industrial city” is thus, at best, a half-truth and at worst a baffling misinterpretation of contemporary urban and regional dynamics, for industrialization remains the primary propulsive force in development everywhere in the contemporary world’; and that theoreticians ‘have tended to overemphasize consumption issues and neglect the urbanization effects of industrial production’. 18

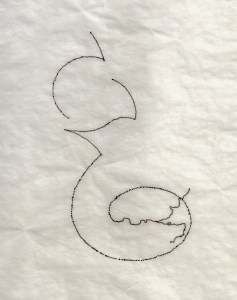

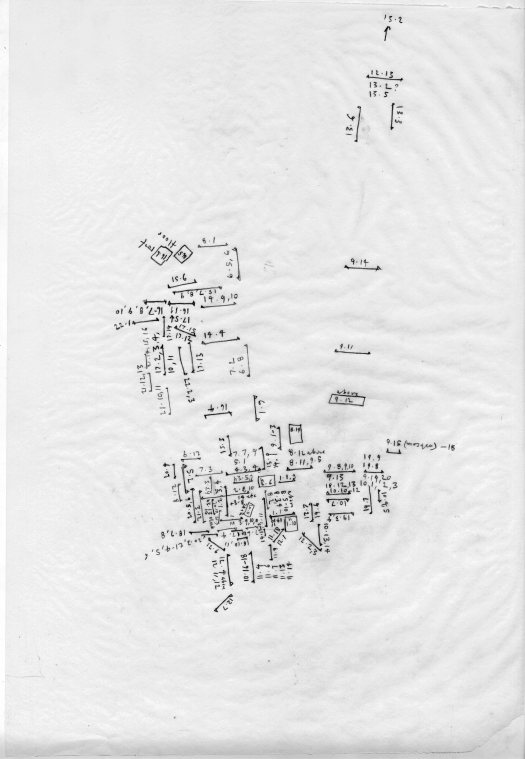

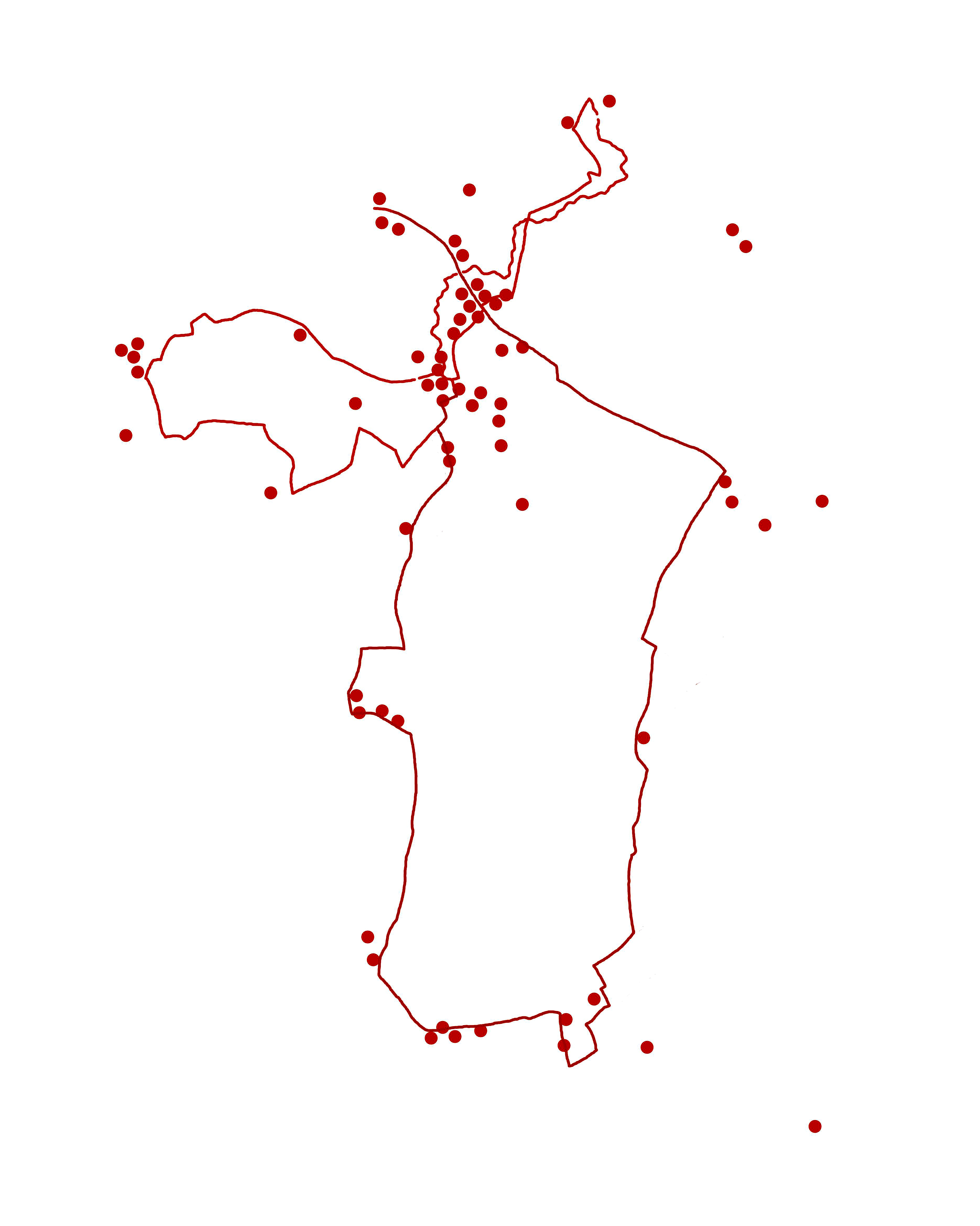

The BBC’s commission to develop Robinson in Space had been confirmed only after I’d mentioned that it would be modelled to some extent on Daniel Defoe’s Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724-26).19 Defoe’s Tour, first published in three volumes over three years, is a series of ‘letters’ each of which describes a more or less serpentine journey through part of the island. Volume I covers East Anglia and England south of London as far as Land’s End; Volume II a journey from Land’s End to London, London itself and the rest of the island south of the rivers Dee and Trent; Volume III everywhere to the north. The tours were perhaps not undertaken as they were described and were at least partly informed by Defoe’s travels in earlier years. Robinson in Space also drew on earlier travels, some undertaken for other films. I had identified places that the film might visit, often from newspaper reports, and had accumulated a large archive of press cuttings filed in chronological order. In the proposal for the film, I arranged selected sites as a series of two-week trips with the camera, between which would be two-week breaks for viewing the previous fortnight’s footage, preliminary editing, and preparation for the next trip. Before each one, I would go through the chronologically filed cuttings, select those relating to the places we were to visit, and put them in a new file in topographical order, so that the film was driven by a kind of data management. There were to be seven trips: the first from Reading,20 to which Robinson, sacked by the University of Barking after publishing his work on London, had exiled himself. From Reading, the two travellers would follow the Thames downstream, supposedly on foot, as far as Sheerness. A second outing from Reading, during which they buy a car, described an arc across southern England to Felixstowe, via Zeebrugge and Calais to Dover, west along the south coast and eventually to Portbury Dock, near Bristol. These and a further five journeys made up an erratic but more or less continuous progress as far as Northumberland.21 The proposal included a schematic drawn on a piece of acetate overlaid on a map. I’d hoped it might resemble Sterne’s narrative lines in Tristram Shandy, but it didn’t look much like any of them.

The film’s ‘problem’ of England wasn’t explicitly stated but, as I wrote after finishing it, ‘there are images of Eton, Oxford and Cambridge, a Rover car plant, the inward investment sites of Toyota and Samsung, a lot of ports, supermarkets, a shopping mall, and other subjects which evoke the by now familiar critique of “gentlemanly capitalism”, which sees the UK’s economic weakness as a result of the City of London’s long term (English) neglect of the (United Kingdom’s) industrial economy, particularly its manufacturing base’.22

This ‘now familiar critique’, already questioned,23 was merely the starting point for the exploration. By the end of the film, its perception of ‘a particularly English kind of capitalism’ had changed: it appeared that the UK’s social and physical ills were not so much the results of gradual ‘decline’ as of the imposition of an economic model, unpleasant to live with but relatively successful in its own terms (a persistent idea of decline, meanwhile, serving to moderate expectations). Also, as Soja observed, the loss of manufacturing had been overstated: a more accurate picture was of a ‘combination of deindustrialization and reindustrialization’.24 Though manufacturing’s share of employment had become smaller, this was at least partly the result of mechanisation, automation, and the reclassifying of some now outsourced tasks as services. Manufacturing had also changed, and was less visible: the UK’s manufacturing’s strengths were in capital goods and intermediate products – neither seen in shops and both often produced in out-of-the-way places – while many branded products, such as those of the UK’s car industry, most of it foreign-owned, were indistinguishable from others of the same makes built abroad.25 It turned out later that the mid-1990s had been a relatively successful period for the UK’s international trade, exports slightly exceeding imports in the years 1995-1997.26

At some point after I had finished Robinson in Space, I began to think – or hope – that, by citing Berger’s critique of narrative I might claim some validity for the film’s peripatetic method. Although its images rarely depart from the order in which they were photographed, I began to see the film as a succession of discontinuous spaces, each one potentially the crossing point of intersecting narratives – a ‘star of lines’ – a thought encouraged by the film’s expansion, later, as a book, in which images and text are accompanied by annotation.27

I began the cinematography for Robinson in Ruins in January 2008. I had by then made two multi-screen installations, assembling moving images simultaneously in space, rather than sequentially in time, as they are in films; each installation an attempt to create a coherent virtual space by displaying footage on screens arranged in a configuration based on that of its various camera viewpoints, so as to mimic, in one, a complex interior…28

Aerial view of Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, Mumbai

Overlay with camera positions in station

Montage of screens on freehand plan of station

…and, in the other, the UK’s urban geography in circa 1900.

Detail from Stanford’s Family Atlas 1894

While making the film, I hoped that it might lead to another installation or a book, perhaps both. It was made as part of a research project,29 a collaboration with Doreen Massey, Patrick Wright, and Matthew Flintham, the project’s doctoral student. The aim was to explore a tension between, on one hand, the extent of critical and cultural attention devoted to experience of mobility and displacement, and, on the other, a tendency to hold on to ideas of dwelling from a more settled, agricultural past. In early discussions, questions about ‘belonging’ gave way to others, more urgent, about enclosure and the absence of rights to land. Doreen discussed this in ‘Landscape/Space/Politics: an essay’, one of her contributions to the project.30

The film is a record of a largely unplanned wandering through part of southern England: as before, the picture was photographed and edited before anything was written, but this time there was no map. I began very tentatively, with an image of a house in Oxford, encased in a temporary structure of scaffolding and plywood.

A few weeks later, after a couple of preliminary excursions, I set out for Newbury where, in 1795, Berkshire magistrates had inaugurated the model of outdoor poor relief known as the Speenhamland system: they had met at the Pelican Inn in Speenhamland, now part of central Newbury.

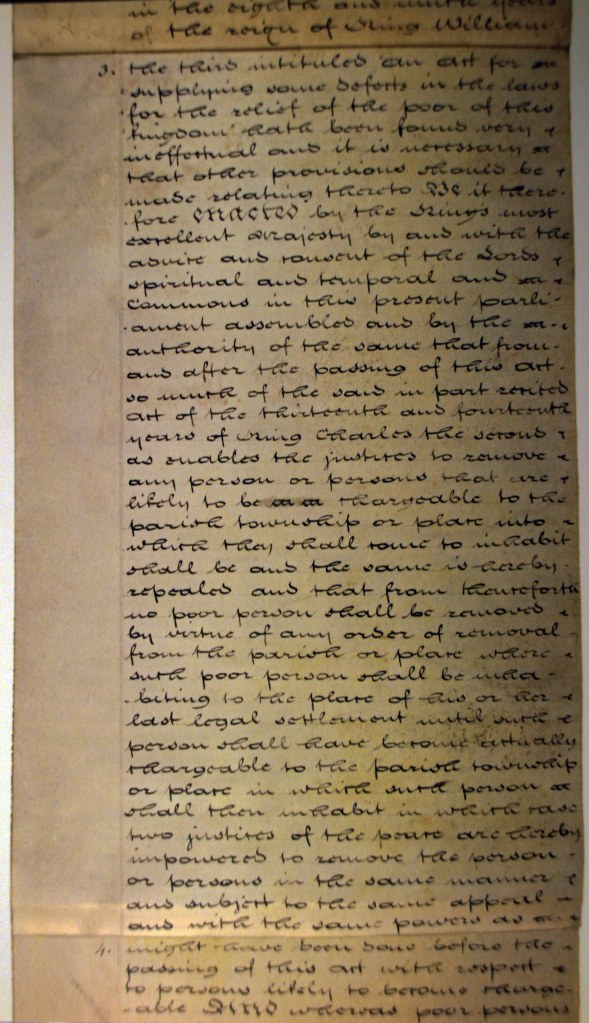

In the same year, the 1662 Settlement Act was amended by An Act to prevent the Removal of Poor Persons until they shall actually become chargeable.

The Act enabled the rural poor to move to factory towns; Speenhamland made it easier to remain on the land. For Karl Polanyi, in The Great Transformation,31 much referred to in the wake of the 2007-8 financial crisis, the ‘double movement’ of the Act and Speenhamland in 1795 was a crucial moment in the imposition of markets, and in a history that led ultimately to twentieth-century catastrophe.

By November, I had made an approximately elliptical anti-clockwise progress though mostly rural landscapes, arriving – soon after the culmination of the crisis – in the vicinity of a place called Enslow, where the former main road from London to Worcester crosses the river Cherwell, about eight miles north of Oxford.32

In For Space, Doreen had written: ‘Perhaps we could imagine space as a simultaneity of stories-so-far.’33 Enslow is not much more than a bridge, a few houses, a roadside pub – ‘The Rock of Gibralter’ – now closed, and some businesses in a former railway yard. For such a small place, it seemed to offer an unusual number of stories,34 though when I suggested this to Doreen, she thought it was perhaps not so unusual.35 Some of these stories are related in the film, in narration accompanying footage supposedly photographed by ‘a man called Robinson’ who, released from prison in January 2008, had ‘made his way to the nearest city, and looked for somewhere to haunt’.36 Towards the end of the film the images are of spaces close together, some of them intervisible, so that with the aid of continuous ambient sound, a sense of surrounding landscape was possible.

In 2011, after the film’s release, I was invited to devise an exhibition at Tate Britain, in which its images and narrative would be accompanied by works from the Tate’s collection, and other items. In discussions with Tate curators and Jamie Fobert, the exhibition’s architect, its design was developed as a succession of seven ‘clusters’, each based on part of the film, to be arranged in the gallery as a circuit modelled on that of the film’s progress through the landscape.37 Each ‘cluster’ was conceived as a crossing point of intersecting narratives, a ‘star’ of lines. As in the earlier multi-screen installations, moving images were displayed simultaneously, rather than sequentially, as they are in the film, and in a layout based on the topography of their subjects. The exhibition opened in March 2012 as The Robinson Institute, and continued until October.38 There was an accompanying book, in which many of the exhibits, and some other works, were reproduced.39

- Louis Aragon, Paris Peasant (Boston: Exact Change, 1994), 113-115. ↩︎

- Patrick Keiller, The View from the Train (London, New York: Verso, 2013). ↩︎

- Walter Benjamin, ‘Surrealism: the Last Snapshot of the European Intelligentsia’, One-Way Street and Other Writings, tr. Edmund Jephcott, Kingsley Shorter (London: NLB, 1979), 225-239, at 227; see also ‘Hashish in Marseille’, One Way Street, 215-222. ↩︎

- The emulsion area of a 16mm cine frame is about 77 square millimetres, compared to the 319 square millimetres of a 35mm Academy ratio cine frame and the 864 square millimetres of 35mm still cameras. ↩︎

- Stonebridge Park (1981, 16mm bw, 21 minutes). ↩︎

- This is more or less how cinema newsreels were produced. ↩︎

- Laurence Sterne, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, Vol. III, Ch. 18. Sterne’s lanthorn is borrowed from Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690), 2.14.9; see also S. Alexander ‘Locke’s Lantern’, Mind 38.150, April 1929, 271 ↩︎

- Sukhdev Sandhu, ‘Ignatius Sancho and Laurence Sterne’, Research in African Literatures 29.4 (1998), 88-105. ↩︎

- Tristram Shandy, Vol. I, Ch. 22. ↩︎

- The film was eventually completed as The End (1986, 16mm bw, 18 minutes). ↩︎

- London (1994, 35mm colour, 85 minutes), Koninck for the British Film Institute. ↩︎

- See Stephen Daniels, ‘Paris Envy: Patrick Keiller’s London’, History Workshop Journal 40, Autumn 1995, 220-222. ↩︎

- Jacques Reda, The Ruins of Paris, tr. Mark Treharne (London: Reaktion, 1996). See also Parisian Fields, ed. Michael Sheringham (London: Reaktion, 1996). The book of Robinson in Space (London: Reaktion, 1999) was the outcome of a conversation begun at this conference. ↩︎

- Robinson in Space (1997, 35mm colour, 82 minutes), Koninck for the BBC in association with the British Film Institute. ↩︎

- Robinson in Ruins (2010, 35mm colour to 2K, 101 minutes), for the Royal College of Art and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. ↩︎

- Edward W Soja, Postmodern Geographies: the Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory (London, New York: Verso, 1989), 22. ↩︎

- Berger’s essay was published first in New Society in 1967, most recently in Landscapes: John Berger on Art, ed. Tom Overton (London, New York: Verso 2016), 165-170, and, as ‘The Changing View of Man in the Portrait’ in anthologies The Moment of Cubism (1969), The Look of Things (1972) and Selected Essays (2001). Punctuation, spelling etc. here are as in The Look of Things. ↩︎

- Postmodern Geographies, 188. ↩︎

- Daniel Defoe, A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain, ed. Pat Rogers (London: Penguin, 1971). ↩︎

- Arthur Rimbaud’s last-known address in England was in Reading. ↩︎

- Bristol to West Bromwich; West Bromwich to Warrington; Warrington to Immingham; Immingham to Menwith Hill, near Harrogate; and Preston to Newcastle upon Tyne. ↩︎

- The View from the Train, 36. Robinson’s project, a commission from ‘a well-known international advertising agency’, was modelled on Anneke Elwes’s 1994 study Nations for Sale, commissioned by the international advertising network DDB Needham, in which she found Britain ‘a dated concept’, difficult ‘to reconcile with reality’, its ‘brand personality’ entrenched in the past. ↩︎

- See, for instance, W. D. Rubinstein, Capitalism, Culture and Decline in Britain, 1750-1990 (London: Routledge, 1993), quoted in the film, and Ellen Meiksins Wood, The Pristine Culture of Capitalism: A Historical Essay on Old Regimes and Modern States (London: Verso, 1991). ↩︎

- Postmodern Geographies, 188. ↩︎

- See ‘Port Statistics’, The View from the Train, 35-49. ↩︎

- See for instance UK Trade, 1948-2019: statistics, House of Commons library briefing paper CBP 8261, 10 December 2020, 8-9. ↩︎

- Robinson in Space (London: Reaktion, 1999), 205. ↩︎

- The largest of these was a 30-screen ‘replica’ of Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus in Mumbai, the headquarters and end station of India’s Central Railway, one of the largest neo-Gothic railway stations in the world. See Vertigo 3.6, Summer 2007, 38-39, 42-43, and patrickkeiller.org/londres-bombay ↩︎

- http://www.landscape.ac.uk/research/largergrants/thefutureoflandscape.aspx; see also Tate Papers 17, Spring 2012, https://www.tate.org.uk/research/tate-papers/17/to-dispel-great-malady-robinson-in-ruins-the-future-of-landscape-and-moving-image ↩︎

- https://thefutureoflandscape.wordpress.com/landscapespacepolitics-an-essay, also an extra on the BFI’s DVD of the film and, abridged, in Atlas: Geography, Architecture and Change in an Interdependent World, eds. Renata Tyszczuk et al. (London: Black Dog, 2012), 90-95. ↩︎

- Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time (Boston: Beacon Press, 2001), first published in 1944. ↩︎

- ‘The Road From London to Aberistwith’, plates 1-3 in John Ogilby’s 1675 Britannia. ↩︎

- Doreen Massey, For Space (London: Sage, 2005), 9. ↩︎

- In 1596, after several poor harvests, ‘Enslow Hill’ was the site of an attempted rising against enclosing landlords. Its leading figure was Bartholomew Steer, a 28-year-old carpenter who lodged at Hampton Gay, a hamlet, since largely deserted, about a mile to the south on the left bank of the river. Its enclosing landlord, Vincent Barry, was among the rebels’ targets. They planned to steal arms, and make their way to London to join with the city’s apprentices, who had rioted during the previous year. Steer called for the rising to assemble at 9 o’clock in the evening of Sunday, 21 November (O.S.), but only three men joined him, and after two hours they all went home. Barry had been told of the plan by one of Steer’s neighbours. After arrest, imprisonment, interrogation under torture, and a trial for treason, two survivors of those judged to have been participants were hanged, drawn and quartered on the hill.

For a more detailed account, see John Walter, Crowds and Popular Politics in Early Modern England (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2006), 73-123.

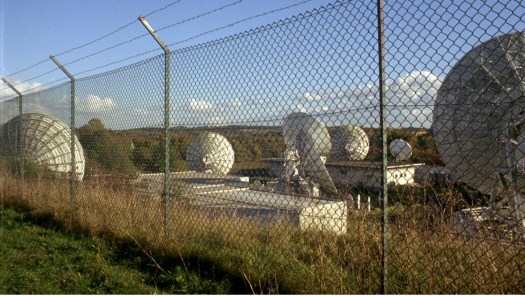

Until recently, the name ‘Enslow Hill’ appeared only in accounts of the rising, all based on records in state papers of suspects’ interrogation. Enslow was then little more than a bridge and a mill; immediately after the bridge, the road diagonally ascends a kind of bluff or promontory extending from higher ground north-west of the river. This is presumed to be Enslow Hill, though it is now known as ‘Gibraltar Point’, a name that perhaps dates from the building of the Oxford Canal. The canal and the Reading to Birmingham railway line follow the Cherwell valley, passing through Enslow east of the river, where there was once a station. The hill was perhaps, as Steer believed, a site of action in an earlier rising in 1549, and is thought to have been the pre-conquest Spelleburge – ‘Speech Hill’ – an Anglo-Saxon meeting place. During the twentieth century, much of it was removed by quarrying; Vodafone’s satellite earth station is now located in the disused quarry. At Hampton Gay, there had been a train crash in 1874, one of the worst ever on a British railway, and several fires at a paper mill; the manor house, built by Vincent Barry’s father, was gutted by fire in 1887, and remains a ruin. I had seen it from the train, but had never visited, or known of the rising, until making the film. On the opposite bank of the river is a similarly small village – Shipton-on-Cherwell – where an enormous limestone quarry, still active, supplied a now-demolished cement works until the 1980s. When owned by Richard Branson, Shipton Manor had been a recording studio. Between 1997 and 2007, Virgin CrossCountry trains passed by. ↩︎ - A thought recently confirmed by Patrick Wright’s The Sea View Has Me Again: Uwe Johnson in Sheerness (Repeater: London, 2020) ↩︎

- The film, on the other hand, was supposed to have been completed by a team of ‘researchers’, who had been given the footage and a notebook after they were discovered in a derelict caravan near the manor house at Hampton Gay. Its narration was informed by the notebook, in which Robinson had written that, from the roof of a car park overlooking Oxford, he had surveyed ‘the location of a Great Malady, that I shall dispel, in the manner of Turner, by making picturesque views, on journeys to sites of scientific and historic interest.’ ↩︎

- https://jamiefobertarchitects.com/work/patrick-keiller/ ↩︎

- https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/patrick-keiller-robinson-institute ↩︎

- The Possibility of Life’s Survival on the Planet (London: Tate Publishing, 2012). ↩︎